4 Machine Learning

The machine learning components of the text segmentation and transcriptions rely on common machine learning algorithms and logic. To better understand these tasks, and how training methods influences the success of these models, I will summarize some of these common building blocks. These are vulgarized and simplified descriptions to increase the broad understanding of these processes, for in depth discussions I refer to the linked articles in the text and machine learning textbooks at the end of this course.

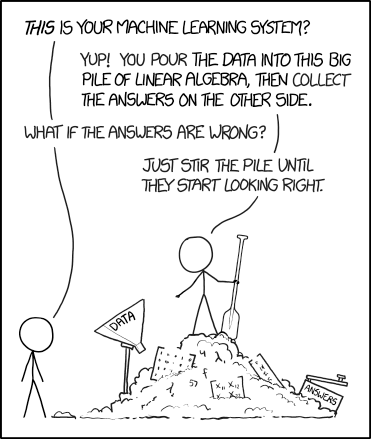

Machine learning models are non-deterministic and rely on learning or training (an optimization method) on ground truth (reference) data. The most simple machine learning algorithm is a simple linear regression. In a simple linear regression one optimizes (trains) a slope and intercept parameter to fit the observed response (ground truth) to explanatory variables (data). For more complex tasks, with more parameters, more data are required. Although oversimplified, the very tongue in cheek cartoon by XKCD (Figure 4.1) is a good mental model of what happens on an abstract level where we shuffle model parameters until we get good correspondence between the data input and the ground truth observations.

From this one can deduce a number of key take-home message:

- a sufficient amount of training data is needed (the pile)

- an appropriate ML and shuffling (optimization) algorithm (stir the pile)

- a ML model is limited by the representations within the training data (we can only tell something about our own pile)

4.0.1 Detecting patterns: convolutional neural networks (CNN)

The analysis of images within the context of machine learning often (but not exclusively) happens using a convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Conceptually a CNN can be seen as taking sequential sections of the image and summarizing them (i.e. convolve them) using a function (a filter), to a lower aggregated resolution (Figure 4.2). This reduces the size of the image, while at the same time while summarizing a certain characteristic, using a filter function. One of the most simple functions would be taking the average value across a 3x3 window.

It is important to understand this concept within the context of text recognition and classification tasks in general. It highlights the fact that ML algorithms do not “understand” (handwritten) text. Where people can make sense of handwritten text by understanding the flow, in addition to recognizing broader patterns, ML approaches focus on patterns, shapes or forms. However, some form of memory can be included using other methods.

4.0.2 Memory and context: recurrent neural networks

A second component to many recognition tasks is a form of memory. Where the CNN encodes for patterns it does so without explicitly taking into account the relative position of these patterns and their relationship to adjacent ones. Here, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks provide a solution. These algorithms allow for some of the information of adjacent data (either in time or space) to be retained to provide context on the current (time or space) position. Both these approaches can be uni- or bi-directional. In the former, the direction of processing matters in the latter it doesn’t. For text recognition the direction does not matter, and it is common to see bi(directional)-LSTM networks in recognition models.

4.0.3 Negative space: connectionist temporal classification

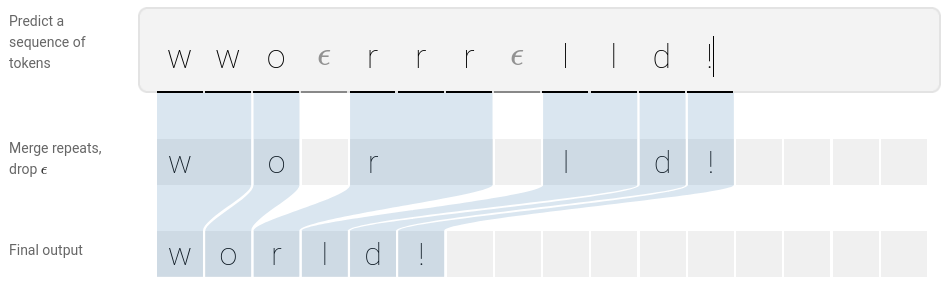

In speech and written text much of the structure is defined not only by what is there, the spoken and written words, but also what is not there, the pauses and spacing. Taken to the extreme the expressionist / dadaist poem “Boem paukeslag” by Paul van Ostaijen is an example of irregularity in typeset text. These irregularities or negative space in the pace of writing is another hurdle for text recognition algorithms. Generally, we want a readable text as output of our ML models not dadaist impressions with large gaps.

These issues in detecting uneven spacing are addressed using the Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC). This function is applied to the RNN and LSTM output, where it collapses a sequence of recurring labels through oversampling to its most likely reduced form.

4.1 The CNN+LSTM+CTC implementation

Putting all the pieces together the most common ML implementation of text segmentation rely heavily on CNN based segmentation networks, while text recognition often if not always takes the form of a CNN + (bidirectional) LSTM/RNN + CTC network. When reading technical documentation on the architecture of models in text transcription frameworks you might come across these terms. Depending on the implementation or framework used data augmentation (see next section) during training might be provided to increase the scope of the model and increase the chances of Out-Of-Distribution (OOD) generalization.

4.2 Transformers

Transformer based OCR (TrOCR) is new breed of HTR algorithms based on the transformer architecture, providing an alternative to the CNN+LSTM+CTT workflow. Unlike the CNN+LSTM+CTC approach TrOCR does not use convolution but chops up an image context window into adjacent subsets combined with a positional (spatio-temporal) marker. Equivalent to the convolutional setup it retains feature and spatio-temporal marker in decoding a sequence.

4.2.0.1 multi-modal LLM

Multi-modal large language models such as ChatGPT leverage the Transformer architecture and use them on an incredibly large scale, using mostly text, but also annotated image data. This allows these LLM (chatbots) to make sense of images of text.